Proctology, part 2 — treatment of acute anal pain

D. Wilhelm, U. Nitsche

When a patient comes to the doctor with acute anal pain ….

In the first part of this article we have already discussed diagnosis and emphasized the importance of patient history in proctology. Once the patient history has been carefully taken, it makes it possible to establish the diagnosis in many cases, or to narrow the possible causes down to a small number. For this reason, and to provide practical guidance, we have therefore decided in this part to classify proctological treatment on the basis of the symptoms the patient presents with at the hospital or at the physician’s office.

Severe, acute-onset pain

The most frequent causes of a pain-related presentation to the proctologist are anal venous thrombosis and anal fissure. Both of these conditions typically result from difficult defecation with heavy straining (anal venous thrombosis) or constipation due to a hard fecal consistency (anal fissure).

The most frequent causes of acute anal pain are anal venous thrombosis and anal fissure.

Both types of pain are described as being “epicritic” — i.e., they are intense in nature and are clearly localizable. Whereas the intensity of pain in anal venous thrombosis declines over the course of a few days, in the case of anal fissure the pain declines over a period of hours, but starts again with every subsequent bowel movement and is usually described as being much more intense. The differential diagnosis includes incarcerated anal prolapse and thrombosed hemorrhoids, but these tend to cause less pain. Anal abscesses are also occasionally a cause of anal pain, but they usually develop slowly and involve dull pain. Neuropathic pain also needs to be considered — e.g., in the context of herpes infection or functional disturbances such as proctalgia fugax.

| Table 1?Frequent causes of anal pain |

|---|

| Anal venous thrombosis |

| Anal fissure |

| Hemorrhoids (prolapse / thrombosis) |

| Perianal abscess |

| Functional disturbances |

| Neuropathic disturbances |

Anal venous thrombosis

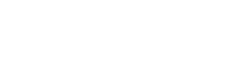

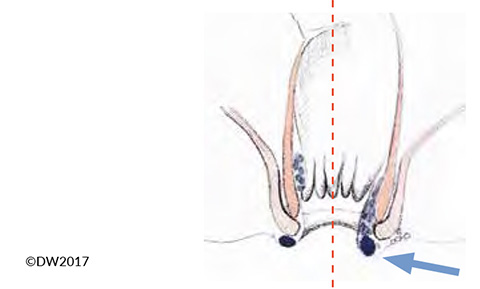

Anal venous thrombosis is caused by a thrombus in the external anal venous plexus (Fig. 1), and is therefore located in the area of the anoderm [1]. A distinction is made between an isolated thrombus and multiple perianal thromboses such as those that often occur during pregnancy. The diagnosis is easy and can be made by inspecting the anal region. The visible thrombus is painful to the touch, usually has a taut consistency, and is covered with anoderm. In the differential diagnosis, it needs to be distinguished from a thrombosed hemorrhoid and incarcerated anal prolapse, but even experienced colleagues may sometimes find it difficult to distinguish from a thrombosed hemorrhoid. If the findings are unclear, we would therefore recommend proctoscopy and differentiation from the hemorrhoid complex.

Treatment of anal venous thrombosis is based on the time course and the extent of the symptoms.

The time of diagnosis is decisive for treatment. The greater the time between the development of the condition and presentation to the physician, organization of the thrombus can occur that makes it more difficult to provide relief with an incision. An incision should therefore only be carried out within the first few days, and the ideal cut-off point is between 1 and 3–4 days [2]. In addition to the time course, the patient’s symptoms should therefore also be taken into account, as well as possible comorbidities (e.g., with anticoagulant medication). The sensitivity of the anoderm and the risk of injuring this important and sensitive area by using inappropriate measures should be emphasized here again.

Fig. 1?Diagram of the anal canal, indicating the internal venous plexus (hemorrhoidal plexus) and external venous plexus.

Fig. 1?Diagram of the anal canal, indicating the internal venous plexus (hemorrhoidal plexus) and external venous plexus.

For the incision, the region involved is infiltrated with local anesthetics and then excised over the thrombosis in a spindle pattern radial to the anus. In most cases, the thrombus prolapses spontaneously, or it can be massaged out with slight pressure. If the thrombus is already organized, excessive manipulation should be avoided. If the patient has a bleeding diathesis, the incision should be closed with a suture (3–0 / 4–0 resorbable suture), but otherwise this is not necessary. The information given to the patient should mention not only that the infiltration/anesthesia may be painful, but also that there is a usually harmless slight tendency to bleed after the intervention. Any allergic reactions to local anesthetics and any patients with a bleeding diathesis should be excluded. The subsequent treatment includes analgetic medication and sitz baths if appropriate.

Without treatment, anal venous thromboses usually heal within 2–3 weeks, and surgical treatment is therefore not in principle required for this basically benign condition. With conservative treatment, local anesthetics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have proved to be useful for reducing pain, and a positive effect of glycerin nitrate and nifedipine ointment has also been reported. In our own practice, protecting the area and elevation of the pelvis have proved their value, leading to rapid subsidence of the swelling. Fecal softeners and hygienic measures can also be recommended [3].

A study published in 2009 analyzed the conservative approach in 72 patients and reported a recurrence rate of 13.9%, with a good response to the suggested treatment [4].

A review published in 2013, comparing different forms of treatment, concluded despite inadequate data that freedom from symptoms is achieved significantly more quickly after excision and surgical relief and that recurrence rates can be clearly reduced (by approx. 5%), although abscesses and fistulas may result in a small percentage of cases [2].

Anal fissure

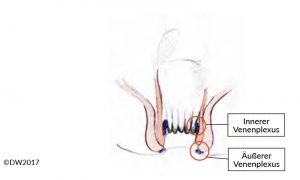

Like anal venous thrombosis, anal fissure is a single-glance diagnosis (or with a proctoscopy examination if needed), and it is easy to diagnose in combination with a typical patient history. The decisive aspect in treatment is to distinguish between acute and chronic anal fissure, which are evident from the time course and also show morphological differences. Whereas a fissure in the acute stage appears as a crevice-like tear in the anoderm, chronic courses lead to hypertrophy of the surrounding structures, demarcated with a hypertrophic anal papilla and a sentinel skin tag [5] (Fig. 2). In addition to acute pain, which almost always provokes anal spasm and constipation, hemorrhage and sometimes a purulent secretion may be seen if there is an accompanying fistula. If a proctoscope is not available (e.g., in the outpatient setting), the clear and easily localizable description of pain by the patient is diagnostically important during the digital rectal examination.

Fig. 2? Anal fissure refers to a superficial tear in the skin on the anal canal. When the condition becomes chronic, a hypertrophic anal papilla and a sentinel skin tag often form. There may also be a fistula to the crypt regions above.

Since pain is the leading symptom and it prevents healing due to secondary spasm in the anal region, the treatment is based on pain reduction. In addition to NSAIDs and local anesthetics (ointment, suppositories), the pronounced pain often requires local infiltration treatment. For this, the affected region should be injected using a thin syringe with a medium to long-term anesthetic agent. In addition, the application of external sphincter-relaxing agents such as a glyceryl trinitrate or topical treatment with the calcium-channel blockers diltiazem or nifedipine can be recommended[6]. Since irritant substances in the feces can aggravate the symptoms, appropriate dietary measures should be pointed out to the patient — and specifically avoidance of coffee, citrus fruit, and hot spices. Relaxing sitz baths can also help relieve symptoms.

Cases of marked anal spasm (in the clinical assessment) also make relaxing the sphincter apparatus more important. This can be achieved with sphincter dilation, which can be done mainly with self-dilation using a cone. Manual dilation can also be carried out even at the time of diagnosis, if the patient permits this during an examination under sedation. However, this should be done gently and with adaptation; excessive dilation as in the Lord procedure should not be attempted [7]. Injecting botulinum toxin is an alternative [8], allowing longer-lasting sphincter weakening. This should be done with two or three injections (20–50 IU) into the external anal sphincter muscle near the fissure, lateral to the anocutaneous line. Assuming appropriate selection of the patients, the results of Botox injection are good, with recurrence rates of around 10–30% and freedom from pain in around 80% of cases after 1 week [6, 9].

Surgical treatment is indicated if any complicating factors are present that might prevent healing with conservative therapy. These include a concomitant fistula, marked sclerosis in the fissure region, and a sentinel skin tag causing retention of feces in the fissure. In our own view, the hypertrophic anal papilla that is often mentioned is evidence of involvement of the crypt region and the presence of a possible fistula [10].

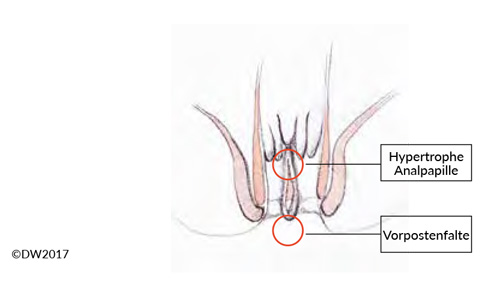

Surgical therapy therefore needs to ensure complete evacuation of the anal canal — i.e., unobstructed passage of feces without retention. Fissurectomy thus requires wide excision of the fissure region well towards the outside and beyond the anocutaneous line. This is a way of ensuring success, but it is also the reason for the postoperative pain that the patient needs to be informed about beforehand.

Fissurectomy does not mean healing the fissure, but it provides the basis for a healing course that takes at least 2–3 weeks.

In fissurectomy, our standard approach is to resect the proximally located anal papilla and adjoining crypt region, so that any possible submucosal fistulas are also removed (prior careful probing of the fissure and crypt region is recommended). The excision should be carried out carefully while protecting the sphincter muscles (Fig. 3). If there is severe sclerosis at the base of the fissure, it can be abraded — e.g., with gentle application of a sharp surgical spoon. Controlled sphincter dilation should form part of every fissurectomy procedure, but this is easily carried out with the patient under anesthesia. Due to the expected postoperative pain, our standard procedure is to already infiltrate the affected region with a long-term anesthetic during the operation.

Fig. 3?Extent of the fissurectomy, which should be continued well towards the outside in order to prevent fecal retention.

The lateral sphincterotomy that used to be recommended in order to reduced excessive sphincter tone should in our view no longer be done, as it involves a risk of incontinence [11], and there are good alternatives available today with botulinum injection [9].

The success rates after fissurectomy are around 95% and can be regarded as very good [12, 13]. Recurrences are usually caused by insufficient excision toward the outside and premature adhesion of the wound edges, and checking during the first few weeks is therefore recommended.

Thrombosed hemorrhoids

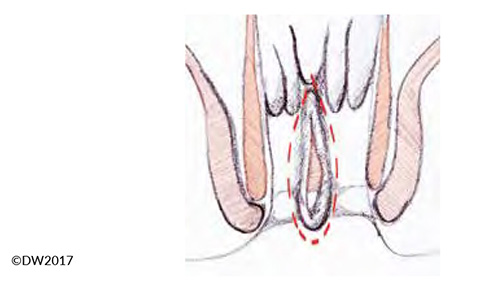

Thrombosis of a hemorrhoid can also cause acute anal pain, but in this case it is not the external but the internal venous plexus that is affected [14]. Differential diagnosis is sometimes difficult versus perianal venous thrombosis, particularly in the presence of grade 3 or grade 4 hemorrhoids, which are visible in the anal canal, but the diagnosis can usually be established clearly on the basis of shiny anal skin and a connection with the hemorrhoid complex evident on proctoscopy (Fig. 4). In principle, the treatment corresponds to that of anal venous thrombosis, but due to the greater bleeding tendency we tend to recommend a more conservative approach and only carry out surgical relief in the acute stage (pain < 24 h) and when there are severe symptoms. Reference may be made to the discussion above regarding the procedure to be used. Conservative treatment also corresponds to the approach with anal venous thrombosis, but we recommend intra-anal repositioning of the affected hemorrhoids and thorough relief and elevation of the pelvis.

Fig. 4?In the presence of hemorrhoid prolapse (arrow), it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between thrombotic anal veins (left) and hemorrhoids (right).

Incarcerated hemorrhoid nodes / prolapse

In addition to thrombosis, incarceration of a hemorrhoid can also cause acute pain, which is usually perceived as less severe and occurs above all in cases of partial or complete anal prolapse. There is diffuse swelling of the affected node, in which the collected blood is not locally as taut and elastic as it is in cases of thrombosis.

The incarcerated node should be gently repositioned if possible during the acute stage and can be retained if necessary with an anal tampon or a rolled-up compress. During repositioning, sufficient time and a gentle approach are necessary, and elevation of the pelvis and local cooling can again be helpful. After successful repositioning, we recommend the patient to keep the node repositioned for another 15–30 min (holding a compress with the pelvis raised) to ensure that the node subsides.

Repositioning may fail in rare cases, and a surgical approach is then required. Due to the acute swelling, there is a risk of excessive resection, and this procedure should therefore only be carried out by an experienced proctologist [1]. Resection should always be considered after successful repositioning, but it can be done electively after 2–3 days.

With regard to the surgical procedure, reference should be made to the subsequent article on anal bleeding, which includes treatment for hemorrhoids.

Perianal abscess

Pain in the anal and perianal region also occurs with perianal abscesses, due to their spatial extent and local inflammation. Depending on the position of the abscess, the pain may be clearly localizable (with superficial abscesses) or may be perceived as dull and compressive (with deep, sometimes supralevator abscesses). The diagnosis is easy with superficial abscesses and can be made on the basis of the localized reddening, swelling, and hyperthermia. When the abscess is deeper, however, diagnosis may also be quite demanding. It is important to remember this, particularly when there are only slight signs of inflammation. If a deep location is suspected, rectoscopy and endosonography should therefore also be carried out — or if these are not available, transcutaneous ultrasound is often sufficient and is also suitable for diagnosing pelvic processes. We only see a need for MRI in exceptional cases; with recurrences or complex fistulas, by contrast, generous use of MRI can be made.

The treatment consists of surgical division of the abscess and drainage, following the basic surgical principle of “ubi pus, ibi evacua.” By contrast, incisions after local anesthesia alone almost always lead to recurrence and should only be carried out in exceptional cases. Surgical revision always involves proctoscopic exploration of the rectum and exclusion of a concomitant fistula. We recommend a generous spindle-shaped incision, which should be made radially to the anus and with a sufficient margin from it, protecting the sphincter muscles. With large, confluent abscesses (e.g., horseshoe abscesses), a counterincision and placement of a drainage tube should be carried out. Postoperative antibiotic administration is not necessary if there is sufficient drainage, but should be considered if there are accompanying phlegmons. If it is not possible to demonstrate the fistula intraoperatively (and this should not be attempted forcibly), then a proctological examination is recommended during the subsequent course and after the accompanying swelling has declined. We will discuss the diagnosis and treatment of fistulas in detail in a separate article.

Neuropathic pain / functional symptoms

Various neurogenic causes can also give rise to acute anal pain, although other pathological findings are sometimes present that can be used to establish the diagnosis or allow further differentiation of the pain characteristics.

Genital manifestations of herpes infection can lead to soreness and itching during the course of the disease, and sometimes to severe pain. This occurs above all when there is rectal involvement in the form of viral proctitis. The diagnosis is easy, due to the typical efflorescence (fluid-filled vesicles) and can be made with a smear or serum antibody test. When there is severe pain, proctoscopy should always be carried out as well. For treatment, oral virostatic treatment — e.g., with aciclovir, valaciclovir, or famciclovir — is recommended [15].

Proctalgia fugax is characterized by sudden-onset pain in the perineal and rectal area, which is sometimes very intense and can last for a few seconds to a maximum of 30 min. The pain does not correlate with defecation, and the patients are free of symptoms between attacks. The diagnosis is based on the typical patient history and exclusion of other possible causes. The pathogenesis of the condition has not been fully clarified, but muscle spasms in the anal region are suspected. There is no specific therapy, but systemic analgesic agents — e.g., Novaminsulfon (BAN, USAN dipyrone; INN metamizole) — can be administered [16, 17].

Levator ani syndrome is another functional disturbance, characterized by spasm of the levator ani muscle and the corresponding pain [18]. The symptoms usually last longer than 30 min and are exacerbated by sitting. The diagnosis is established clinically, with evidence of persistent tension of the levator ani muscle during the digital rectal examination. Asynergy of the pelvic floor muscles and sphincter spasm are also often present. Defecography can also be informative for an experienced examiner. The treatment consists of warm sitz baths, muscle-relaxant medication, anal massage, and biofeedback training. The latter can provide symptomatic therapy in more than 80% of cases and is therefore the treatment of choice [19].

The condition known as anismus (dyssynergic defecation) is related to levator ani syndrome. It is a chronic spasm of the sphincter muscle that leads to continual pain and anorectal outlet obstruction [20]. The diagnosis is established clinically and using anal manometry, but the markedly increased sphincter tone and lack of relaxation during pressing is already noticeable during the digital examination. The diagnostic work-up should exclude other possible causes (particularly fissure), and the treatment involves muscle-relaxant ointments (glyceryl trinitrate, diltiazem, and nifedipine) and Botox injection, which achieves a reduction in muscle tone that lasts for up to 3 months [21]. Biofeedback training is also important in this condition.

Summary

Acute anal pain is a frequent reason for patients to consult a proctologist or endoscopist. The cause is usually anal venous thrombosis or anal fissure, or a disease of the hemorrhoid complex. Inflammations and abscesses also lead to pain, but with these the pain is usually milder and increases more slowly. Functional disturbances or neuropathic changes are present less often. Treatment consists of conservative measures such as the administration of analgetic agents and relaxants, as well as surgical therapy.

References

- Hardy A, Cohen CR. The acute management of haemorrhoids. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England 2014;96:508-11.

- Chan KK, Arthur JD. External haemorrhoidal thrombosis: evidence for current management. Techniques in coloproctology 2013;17:21-5.

- Greenspon J, Williams SB, Young HA, Orkin BA. Thrombosed external hemorrhoids: outcome after conservative or surgical management. Diseases of the colon and rectum 2004;47:1493-8.

- Gebbensleben O, Hilger Y, Rohde H. Do we at all need surgery to treat thrombosed external hemorrhoids? Results of a prospective cohort study. Clinical and experimental gastroenterology 2009;2:69-74.

- Heitland W. [Perianal fistula and anal fissure]. Der Chirurg; Zeitschrift fur alle Gebiete der operativen Medizen 2012;83:1033-9.

- Nelson RL, Thomas K, Morgan J, Jones A. Non surgical therapy for anal fissure. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2012:CD003431.

- O’Connor JJ. Lord procedure for treatment of postpartum hemorrhoids and fissures. Obstetrics and gynecology 1980;55:747-8.

- Simms HN, McCallion K, Wallace W, Campbell WJ, Calvert H, Moorehead RJ. Efficacy of botulinum toxin in chronic anal fissure. Irish journal of medical science 2004;173:188-90.

- Chen HL, Woo XB, Wang HS, et al. Botulinum toxin injection versus lateral internal sphincterotomy for chronic anal fissure: a meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Techniques in coloproctology 2014;18:693-8.

- Herzig DO, Lu KC. Anal fissure. The Surgical clinics of North America 2010;90:33-44, Table of Contents.

- Hasse C, Brune M, Bachmann S, Lorenz W, Rothmund M, Sitter H. [Lateral, partial sphincter myotomy as therapy of chronic anal fissue. Long-term outcome of an epidemiological cohort study]. Der Chirurg; Zeitschrift fur alle Gebiete der operativen Medizen 2004;75:160-7.

- Abramowitz L, Bouchard D, Souffran M, et al. Sphincter-sparing anal-fissure surgery: a 1-year prospective, observational, multicentre study of fissurectomy with anoplasty. Colorectal disease : the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland 2013;15:359-67.

- Aigner F, Conrad F. Fissurectomy for treatment of chronic anal fissures. Diseases of the colon and rectum 2008;51:1163; author reply 4.

- Lohsiriwat V. Anorectal emergencies. World journal of gastroenterology 2016;22:5867-78.

- Wienert V. [Virus-induced anorectal diseases. Condylomata acuminata and herpes simplex]. Der Hautarzt; Zeitschrift fur Dermatologie, Venerologie, und verwandte Gebiete 2004;55:248-53.

- Rao SS, Bharucha AE, Chiarioni G, et al. Functional Anorectal Disorders. Gastroenterology 2016.

- Jeyarajah S, Chow A, Ziprin P, Tilney H, Purkayastha S. Proctalgia fugax, an evidence-based management pathway. International journal of colorectal disease 2010;25:1037-46.

- Grant SR, Salvati EP, Rubin RJ. Levator syndrome: an analysis of 316 cases. Diseases of the colon and rectum 1975;18:161-3.

- Chiarioni G, Nardo A, Vantini I, Romito A, Whitehead WE. Biofeedback is superior to electrogalvanic stimulation and massage for treatment of levator ani syndrome. Gastroenterology 2010;138:1321-9.

- Andromanakos N, Skandalakis P, Troupis T, Filippou D. Constipation of anorectal outlet obstruction: pathophysiology, evaluation and management. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology 2006;21:638-46.

- Emile SH, Elfeki HA, Elbanna HG, et al. Efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin in treatment of anismus: A systematic review. World journal of gastrointestinal pharmacology and therapeutics 2016;7:453-62.