Low-grade Dysplasie beim Barrett-Ösophagus – Zweitmeinung ist wichtig, dann aber therapieren

Thomas Rösch, Hamburg

15Gut 2015;64: 700-706

| Barrett’s oesophagus patients with low-grade dysplasia can be accurately risk-stratified after histological review by an expert pathology panel |

| Lucas C Duits, K Nadine Phoa, Wouter L Curvers, Fiebo J W ten Kate, Gerrit A Meijer, Cees A Seldenrijk, G Johan Offerhaus, Mike Visser, Sybren L Meijer, Kausilia K Krishnadath, Jan G P Tijssen, Rosalie C Mallant-Hent, Jacques J G H M Bergman |

Objective

Reported malignant progression rates for low-grade dysplasia (LGD) in Barrett’s oesophagus (BO) vary widely. Expert histological review of LGD is advised, but limited data are available on its clinical value. This retrospective cohort study aimed to determine the valueof an expert pathology panel organised in the Dutch Barrett’s Advisory Committee (BAC) by investigating the incidence rates of high-grade dysplasia (HGD) and oesophageal adenocarcinoma (OAC) after experthistological review of LGD.

Design

We included all BO cases referred to the BAC for histological review of LGD diagnosed between 2000 and 2011. The diagnosis of the expert panel was relatedto the histological outcome during endoscopic follow-up.Primary endpoint was development of HGD or OAC.

Results

293 LGD patients (76% men; mean 63 years ±11.9) were included. Following histological review, 73% was downstaged to non-dysplastic BO (NDBO) or indefinite for dysplasia (IND). In 27% the initial LGD diagnosis was confirmed. Endoscopic follow-up was performed in 264 patients (90%) with a median followup of 39 months (IQR 16–72). For confirmed LGD, the risk of HGD/OAC was 9.1% per patient-year. Patients downstaged to NDBO or IND had a malignant progression risk of 0.6% and 0.9% per patient-year, respectively.

Conclusions

Confirmed LGD in BO has a markedly increased risk of malignant progression. However, the vast majority of patients with community LGD will be downstaged after expert review and have a low progression risk. Therefore, all BO patients with LGD should undergo expert histological review of the diagnosis for adequate risk stratification.

JAMA. 2014;311:1209-1217

| Radiofrequency Ablation vs Endoscopic Surveillance for Patients With Barrett Esophagus and Low-Grade Dysplasia A Randomized Clinical Trial |

| K. Nadine Phoa, MD; Frederike G. I. van Vilsteren, MD; Bas L. A. M.Weusten, MD; Raf Bisschops, MD; Erik J. Schoon, MD; Krish Ragunath, MD; Grant Fullarton, MD; Massimiliano Di Pietro, MD; Narayanasamy Ravi, MD; Mike Visser, MD; G. Johan Offerhaus, MD; Cees A. Seldenrijk, MD; Sybren L. Meijer, MD; Fiebo J.W. ten Kate, MD; Jan G. P. Tijssen, PhD; Jacques J. G. H.M. Bergman, MD, PhD |

Importance

Barrett esophagus containing low-grade dysplasia is associated with an increased risk of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma, a cancer with a rapidly increasing incidence in the western world.

Objective

To investigate whether endoscopic radiofrequency ablation could decrease the rate of neoplastic progression.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Multicenter randomized clinical trial that enrolled 136 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of Barrett esophagus containing low-grade dysplasia at 9 European sites between June 2007 and June 2011. Patient follow-up ended May 2013.

Interventions

Eligible patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either endoscopic treatment with radiofrequency ablation (ablation) or endoscopic surveillance (control). Ablation was performed with the balloon device for circumferential ablation of the esophagus or the focal device for targeted ablation, with a maximum of 5 sessions allowed.

Main Outcomes and Measure

The primary outcomewas neoplastic progression to high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma during a 3-year follow-up since randomization. Secondary outcomes were complete eradication of dysplasia and intestinal metaplasia and adverse events.

Results

Sixty-eight patients were randomized to receive ablation and 68 to receive control. Ablation reduced the risk of progression to high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma by 25.0%(1.5%for ablation vs 26.5%for control; 95%CI, 14.1%-35.9%; P < .001) and the risk of progression to adenocarcinoma by 7.4%(1.5%for ablation vs 8.8% for control; 95%CI, 0%-14.7%; P = .03). Among patients in the ablation group, complete eradication occurred in 92.6%for dysplasia and 88.2%for intestinal metaplasia compared with 27.9%for dysplasia and 0.0%for intestinal metaplasia among patients in the control group (P < .001). Treatment-related adverse events occurred in 19.1%of patients receiving ablation (P < .001). The most common adverse event was stricture, occurring in 8 patients receiving ablation (11.8%), all resolved by endoscopic dilation (median, 1 session). The data and safety monitoring board recommended early termination of the trial due to superiority of ablation for the primary outcome and the potential for patient safety issues if the trial continued.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this randomized trial of patients with Barrett esophagus and a confirmed diagnosis of low-grade dysplasia, radiofrequency ablation resulted in a reduced risk of neoplastic progression over 3 years of follow-up.

Gastroenterology 2015;online (doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.013.)

| Radiofrequency Ablation is Associated with Decreased Neoplastic Progression in Patients with Barrett’s Esophagus and Confirmed Low-Grade Dysplasia |

| Aaron J. Small, MD, MSCE, James L. Araujo, MD, Cadman L. Leggett, MD, Aaron H. Mendelson, MD, Anant Agarwalla, MD, Julian A. Abrams, MD, MPH, Charles J. Lightdale, MD, Timothy C. Wang, MD, Prasad G. Iyer, MD, MS, Kenneth K. Wang, MD, Anil K. Rustgi, MD, Gregory G. Ginsberg, MD, Kimberly A. Forde, MD, MHS, Phyllis A. Gimotty, PhD, James D. Lewis, MD, MSCE, Gary W. Falk, MD, MS, Meenakshi Bewtra, MD, MPH, PhD |

Background & Aims

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) with low-grade dysplasia (LGD) can progress to high-grade dysplasia (HGD) and esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) has been shown to be an effective treatment for LGD in clinical trials but its effectiveness in clinical practice is unclear. We compared the rate of progression of LGD following RFA to that with endoscopic surveillance alone in routine clinical practice.

Methods

We performed a retrospective study of patients who either underwent RFA (n=45) or surveillance endoscopy (n=125) for LGD, confirmed by at least 1 expert pathologist, from October 1992 through December 2013 at 3 medical centers in the US. Cox regression analysis was used to assess the association between progression and RFA.

Results

Data were collected over median follow-up periods of 889 days (inter-quartile range, 264–1623 days) after RFA and 848 days (inter-quartile range, 322–2355 days) after surveillance endoscopy (P=.32). The annual rates of progression to HGD or EAC was 6.6% in the surveillance group and 0.77% in the RFA group. The risk of progression to HGD or EAC was significantly lower among patients who underwent RFA than those who underwent surveillance (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.06; 95% confidence interval, 0.008–0.48).

Conclusions

Among patients with BE and confirmed LGD, rates of progression to a combined endpoint of HGD and EAC were lower among those treated with RFA than among untreated patients. Although selection bias cannot be excluded, these findings provide additional evidence for the use of endoscopic ablation therapy for LGD.

Was Sie hierzu wissen müssen

Die niedriggradige Dysplasie (LGIN low grade intraepitheliale Neoplasie) ist histopathologisch schwer von einer Entzündung abzugrenzen; so liegen Interobserver-Varianzen bei kappa-Werten meist unter 0.4 (1-5), was einer schlechten Interobserver-Varianz entspricht. Die Arbeitsgruppe aus Amsterdam hatte bereits in einer vorherigen Arbeit gezeigt, dass von 147 LGIN-Diagnosen aus Pathologie-Praxen sich bei Nachbefundung durch spezialisierte GI-Pathologen nur in 15% bestätigte. Diese 15% Patienten entwickelten allerdings in 85% im weiteren Follow-up (im Mittel 9 Jahre) höhergradige Neoplasien (high grade IN oder Karzinom), was bei den restlichen 85% nur in 4.6% der Fall war (6).

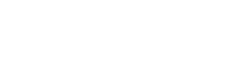

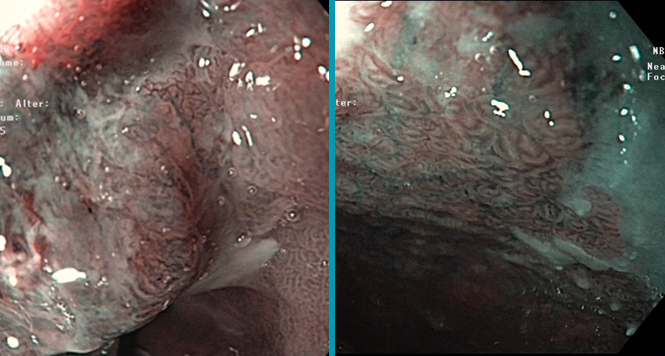

Die vorgestellte Multizenter-Studie aus Amsterdam zeigte erneut, dass histopathologisch bestätigte LGIN ein jährliches Progressionsrisiko von 9.1% zeigten (7); hier wurden 293 LGIN-Patienten, die einem Pathologie-Expertenpanel vorgestellt wurden, zweitbeurteilt und es wurde in 27% die Diagnose bestätigt, also etwas häufiger. Im mittleren Follow-up (36 Monate; 90% Follow-up-Rate) entwickelten die bestätigten Diagnosen 10 mal häufiger höhergradige Neoplasien als die restlichen (0.6-0.9% pro Jahr). Allerdings liegen von den jeweiligen initialen und Follow-up-Endoskopien nur rudimentäre Befunde vor (Datum, „endoscopic landmarks“, Zahl der Biopsien), sodass nicht klar war, wie viele Patienten endoskopisch sichtbare Läsionen hatten, was einer der wenigen Schwachpunkte der Studie darstellt. Die Zahl der Follow-up-Endoskopien betrug im Median 2, und es wurden im Mittel bei einer durchschnittlichen Barrett-Länge von 4 cm, 8 Biopsien entnommen, also eine gute Adhärenz zu Leitlinien.

Ob Patienten mit Barrett und LGIN also therapiert werden sollen, hängt also entscheidend davon ab, ob die Histopathologie durch Zweitmeinung bestätigt wird; zudem spielt auch der endoskopische Aspekt eine Rolle (worauf in den Studien aus Amsterdam allerdings nicht eingegangen wird). Die Resultate einer vor 1 Jahr erschienen randomisierten Studie aus Amsterdam zeigen, dass die Radiofrequenzablation des Barrett bei Vorliegen einer bestätigten LGIN die Progressionsrate entscheidend abbremst (8). Patienten mit endoskopisch sichtbaren Läsionen wurden im Übrigen ausgeschlossen. Die Ergebnisse im einzelnen:

| Ablationsgruppe (n=68) |

Kontrollen (n=68) |

Risikoreduktion | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Progression zu HGIN/Karzinom | 1.5% | 26.5% | 25% |

| Progression zu Karzinom | 1.5% | 8.8% | 7.4% |

| Beide Unterschiede sind signifikant | |||

| Therapieerfolg in der RFA-Gruppe (im Median 3 Sitzungen) | |||

| Komplette Eradikation | Dysplasie initial | 92.6% | |

| Dysplasie und Barrett initial | 88.2% | ||

| Dysplasie im Follow-up | 98.4% | ||

| Dysplasie und Barrett im Follow-up | 90.0% | ||

Einschränkend muss allerdings gesagt werden, dass die guten Ergebnisse der Amsterdamer Gruppe plus Studienpartnern nicht von allen Gruppen nachvollzogen werden konnten, in der Routine liegen Ablationsraten niedriger und Rezidivraten höher (9-14), und in den Studien mit guten Langzeit-Ergebnissen ist teilweise im Kleingedruckten zu lesen, dass 55% der Patienten nach Erreichen des Endpunktes erneut mit Radiofrequenz behandelt wurden, in 62% davon ohne histologische Bestätigung (15). Wenn man also andauernd nachbehandelt, sind die Ergebnisse natürlich besser.

Diese Ergebnisse wurden jetzt in einer retrospektiven nicht-randomisierten Studie aus den USA bestätigt, allerdings in einer steilen Abwärtsspirale in der Evidenzgradierung. Es ist erstaunlich dass diese relativ kleine retrospektive und nicht-randomisierte Multizenter-Studie über 11 Jahren aus drei US-Zentren in der Zeitschrift Gastroenterology angenommen wurde. In einem Follow-up-Zeitraum von nur 2.5 Jahren lagen die Progressionsraten bei 6.6% (LGIN, n=45) versus 0.8% (Kontrollen, n=123). Soweit man aus den Befunden schließen kann, hatten 3 Patienten in der Ablations- und 13 Patienten in der Kontrollgruppe fokale noduläre Läsionen in der Endoskopie, ein Teil davon auch eine EMR; diese Patienten hätten eigentlich herausgenommen werden müssen. Also eine methodisch eher schwache Verstärkung der Evidenz, die Ergebnisse gehen aber in dieselbe Richtung.

Literatur

- Wani S, Falk GW, Post J, et al. Risk factors for progression of low-grade dysplasia in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology 2011;141:1179–86, 1186

- Skacel M, Petras RE, Gramlich TL, et al. The diagnosis of low-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus and its implications for disease progression. Am J Gastroenterol2000;95:3383–7.

- Wani S, Mathur SC, Curvers WL, et al. Greater interobserver agreement by endoscopic mucosal resection than biopsy samples in Barrett’s dysplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;8:783–8.

- Coco DP, Goldblum JR, Hornick JL, et al. Interobserver variability in the diagnosis of crypt dysplasia in Barrett esophagus. Am J Surg Pathol 2011;35:45–54.

- Voltaggio L, Montgomery EA, Lam-Himlin D. A clinical and histopathologic focus on Barrett esophagus and Barrett-related dysplasia. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011 Oct;135(10):1249-60.

- Curvers WL, ten Kate FJ, Krishnadath KK, Visser M, Elzer B, Baak LC, Bohmer C, Mallant-Hent RC, van Oijen A, Naber AH, Scholten P, Busch OR, Blaauwgeers HG, Meijer GA, Bergman JJ. Low-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: overdiagnosed and underestimated. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Jul;105(7):1523-30. Epub 2010 May 11.

- Duits LC, Phoa KN, Curvers WL, Ten Kate FJ, Meijer GA, Seldenrijk CA, Offerhaus GJ, Visser M, Meijer SL, Krishnadath KK, Tijssen JG, Mallant-Hent RC, Bergman JJ. Barrett’s oesophagus patients with low-grade dysplasia can be accurately risk-stratified after histological review by an expert pathology panel.Gut. 2015 May;64(5):700-6. Epub 2014 Jul 17.

- Phoa KN, van Vilsteren FG, Weusten BL, Bisschops R, Schoon EJ, Ragunath K, Fullarton G, Di Pietro M, Ravi N, Visser M, Offerhaus GJ, Seldenrijk CA, Meijer SL, ten Kate FJ, Tijssen JG, Bergman JJ. Radiofrequency ablation vs endoscopic surveillance for patients with Barrett esophagus and low-grade dysplasia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014 Mar 26;311(12):1209-17.

- Orman ES, Li N, Shaheen NJ. Efficacy and durability of radiofrequency ablation for Barrett’s Esophagus: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Oct;11(10):1245-55. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.03.039. Epub 2013 May 2.

- Lee JK, Cameron RG, Binmoeller KF, Shah JN, Shergill A, Garcia-Kennedy R, Bhat YM. Recurrence of subsquamous dysplasia and carcinoma after successful endoscopic and radiofrequency ablation therapy for dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus. Endoscopy. 2013 Jul;45(7):571-4. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1326419. Epub 2013 Apr 16.

- Gupta M, Iyer PG, Lutzke L, Gorospe EC, Abrams JA, Falk GW, Ginsberg GG, Rustgi AK, Lightdale CJ, Wang TC, Fudman DI, Poneros JM, Wang KK. Recurrence of esophageal intestinal metaplasia after endoscopic mucosal resection and radiofrequency ablation of Barrett’s esophagus: results from a US Multicenter Consortium. Gastroenterology. 2013 Jul;145(1):79-86.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.03.008. Epub 2013 Mar 15.

- Guarner-Argente C, Buoncristiano T, Furth EE, Falk GW, Ginsberg GG. Long-term outcomes of patients with Barrett’s esophagus and high-grade dysplasia or early cancer treated with endoluminal therapies with intention to complete eradication. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013 Feb;77(2):190-9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.10.013.

- Dulai PS, Pohl H, Levenick JM, Gordon SR, MacKenzie TA, Rothstein RI. Radiofrequency ablation for long- and ultralong-segment Barrett’s esophagus: a comparative long-term follow-up study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013 Apr;77(4):534-41. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.10.021. Epub 2013 Jan 3.

- Orman ES, Kim HP, Bulsiewicz WJ, Cotton CC, Dellon ES, Spacek MB, Chen X, Madanick RD, Pasricha S, Shaheen NJ. Intestinal metaplasia recurs infrequently in patients successfully treated for Barrett’s esophagus with radiofrequency ablation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 Feb;108(2):187-95; quiz 196. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.413. Epub 2012 Dec 18.

- Shaheen NJ, Overholt BF, Sampliner RE, Wolfsen HC, Wang KK, Fleischer DE, Sharma VK, Eisen GM, Fennerty MB, Hunter JG, Bronner MP, Goldblum JR, Bennett AE, Mashimo H, Rothstein RI, Gordon SR, Edmundowicz SA, Madanick RD, Peery AF, Muthusamy VR, Chang KJ, Kimmey MB, Spechler SJ, Siddiqui AA, Souza RF, Infantolino A, Dumot JA, Falk GW, Galanko JA, Jobe BA, Hawes RH, Hoffman BJ, Sharma P, Chak A, Lightdale CJ. Durability of radiofrequency ablation in Barrett’s esophagus with dysplasia. Gastroenterology. 2011 Aug;141(2):460-8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.061. Epub 2011 May 6.